Editor’s Note: The Institute for Local Self Reliance (ILSR) works to debunk myths that community broadband presents failure for local governments that pursue public Internet networks.

This article was originally published on ILSR’s MuniNetworks.org.

Incumbent telephone and cable companies, as well as a variety of anti-government think tanks, frequently label community broadband networks as failures. The truth is that the vast majority of community broadband networks, particularly fiber-to-the-home networks, have tremendously benefited their community. Telco and cableco slurs against them are predicated on ignorance; they assume that most people will not independently research the supposed failures.

Though we have looked into these accusations and debunked them, our position is not that every community has built a flawless network or that every community should immediately invest in fiber-to-the-home. Rather, we recognize that what is right for one community may not be right for another.

Ultimately, the community itself must decide what is important and how to proceed.

But for those who need proof that community networks have been incredibly successful, we documented the superiority of community fiber networks in North Carolina compared to the big incumbents they compete against:

Network Economics

One of the most common attacks is for anti-government groups to say that public networks in the U.S. have collectively lost hundreds of millions of dollars, or that specific networks have never made a profit, or to otherwise suggest that publicly owned systems inevitably raise taxes.

This is total misinformation. The box [below] explains some basic economics behind these networks, but the key is that any large network has a business plan that calls for losing money in the early years. The network has many expenses before it starts selling services. Even once it has started hooking up customers, it may take years to hook up all the customers that immediately want service. Paying down these early costs takes years - but if there were an easier way, you can bet the private sector would be doing it. Unfortunately, building essential infrastructure is inevitably an expensive long term investment.

Claiming that a network is a failure because it loses money for the first five years is nonsense and betrays a total ignorance of the business model behind large broadband networks.

To say that there is something unusual about this is analogous to saying that even though a homeowner has made payments on his or her 30-year mortgage in a timely manner during the first 15 years of its term, the fact that the mortgage is not paid off means the borrower is financially insolvent and never should have taken the mortgage out in the first place.Source: Paying the Bills, Measuring the Savings

The numbers are meant to scare people into supporting the continuation of a monopoly or duopoly.

We know that community broadband networks get tremendous take rates:

In the case of muni systems, which are not-for-profit enterprises, one measure of “success” is defined as the level of their “take rate,” that is, the percentage of potential subscribers who are offered the service that actually do subscribe. Nationwide, the take rates for retail municipal systems after one to four years of operation averages 54 percent. This is much higher than larger incumbent service provider take rates, and is also well above the typical FTTH business plan usually requiring a 30-40 percent take rate to “break even” with payback periods.Source: Municipal Fiber to the Home Deployments: Next Generation Broadband as a Municipal Utility

One of the reasons the take-rates are so impressive is because these networks are typically built where there is a great need for broadband. Another reason is that some of these networks offer the fastest speeds available in the U.S. at affordable prices.

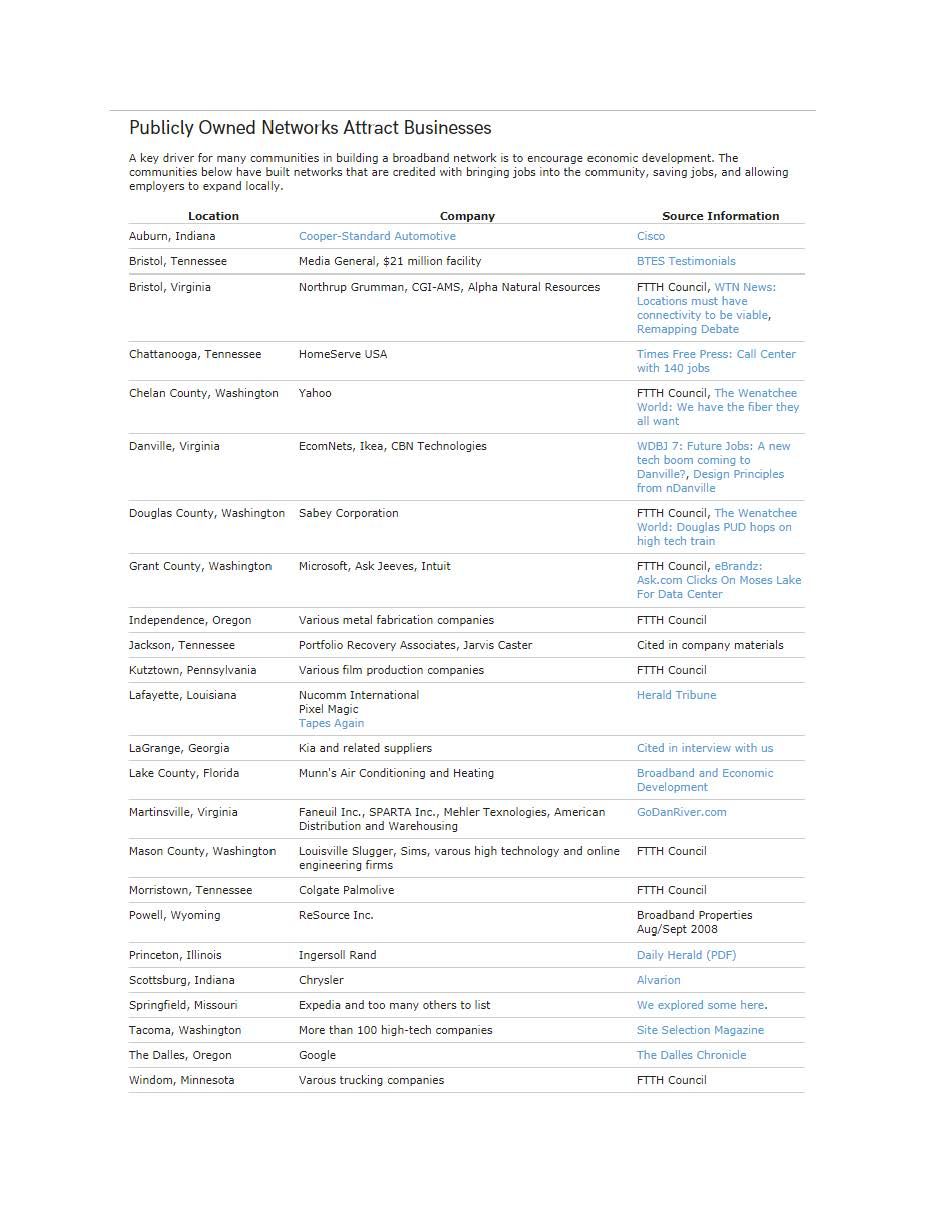

Publicly Owned Networks Attract Businesses

A key driver for many communities in building a broadband network is to encourage economic development. The communities [in the chart following this article] have built networks that are credited with bringing jobs into the community, saving jobs, and allowing employers to expand locally.

Benefits Beyond Dollars

As a final note in this section on community broadband in general, the intense focus on how long a network takes to break even or generate net income misses many of the ancillary benefits from community networks. Those most loudly attacking the networks have frequently not even spoken to anyone from the community and base their criticism entirely on a few financial documents that they generally misinterpret and that rarely tell the whole story. See our discussion about the difference between public and private balance sheets to learn why it is important to consider more than just financial data in evaluating these networks.

Community networks are often demonized by massive cable and telephone companies for “failing” when they do not create profits in the first 3 years. But it hard to imagine a worse way of measuring success. The goal of the network is to increase economic development, ensure a higher quality of life, and generally produce a variety of indirect benefits that are extremely difficult to measure -- if anyone were even to try (most do not).Few demand that local governments turn a profit on the roads they manage within 3 years of building them. It makes no more sense to make such a demand of community networks.

Source: Broadband Payback Not Just About Subscriber Revenues

Learning From Mistakes

All community broadband networks are clearly not failures. The claim is absurd. However, there are some communities that are most frequently cited as failures by critics (who often have never taken the time to speak with people from the community).

- iProvo suffered from many problems and was ultimately sold to a private company. However, iProvo was also unique in a number of areas (and certainly produced some benefits for the community). As a result of incumbent-protection legislation from the state, iProvo had to use a pure open-access model, which means it could not directly offer any services. Though some communities in the U.S. have found ways to make this work, most do not even attempt the model because offering direct services is generally required to generate sufficient revenue to pay down the debt from the system.Aside from using a rare model (also a fiber-optics technology that most community broadband networks have not used), iProvo and other early networks made mistakes from which everyone has learned and few repeat. Thus, even though iProvo did not succeed, there is no reason to believe other community broadband networks would fail.

- Another network commonly cited as a failure is the Ashland Fiber Network (AFN) in Oregon. Ashland also made a number of mistakes, which communities across the country have learned from. But Ashland has fixed many of the problems and the network has benefited the city - read more about the turn-around here.

Remember, incumbent telephone and cable companies go to great effort and expense to discredit these systems because they are intimidated by the threat of competition. If these networks really failed as they claim, they would not spend so much to fight them. Remember, no one fights incompetent competition.