‘Why can we find millions for massive infrastructure projects, but can’t get the sidewalks fixed?’ When Charles Marohn, a civil engineer, land use planner and founder of Strong Towns, first begins to answer that question he explains that the more American cities grow, the poorer they become.

Marohn gave his curbside chat to a packed ballroom at ICMA 2018 in Baltimore, explaining in visual detail, how local governments can’t absorb the costs of modern land use decisions. Growth patterns have proved to reduce wealth in city after city, Marohn said. Some have gone insolvent as a result, while others approach “soft default.”

Strong Towns engages with mayors and civic leaders nationwide and shows them that their most profitable areas are neither the big box store on the fringe of the city, nor the cul de sac single-family residential enclaves that characterize community and economic development for several decades. By showing local government leaders lost revenue value behind development patterns, Marohn told Gov1 he hopes to change land use so in 20-30 years cities are not suffering “deep regrets.”

The History of Short-Term Revenues & Long-Term Liabilities

After World War II, American cities entered a new era of development-fueled growth. But Marohn explained the facade: the roll of short-term financial gains result in eventual default. Modern land use decisions impose maintenance costs that cities cannot afford over the long-term.

Local governments generally pay little of upfront development cost for new buildings, roads and utilities. The additional tax revenue is generated quickly at a very low cost. The cumulative cash flow looks good – and cities keep expanding to increase revenues.

However, in exchange, cities agree to the long-term repair, service and maintenance of the necessary infrastructure to maintain new development. That’s where the bleeding begins. Cities are finding that these long-term public maintenance costs take decades to recoup financially.

“Local governments are exchanging a short-term benefit in cash for a long-term liability,” he wrote in Illusion of Wealth in 2015.

Big box developments and modern residential zoning are eviscerating the solvency of cities like Lafayette, Louisiana. There’s 10 times the amount of water pipe per person since 1949, though the population has grown 3.5 percent. The city of about 125,000 was going broke when they began working with Marohn and Strong Town a few years ago.

What Strong Towns discovered was that Lafayette’s newer developments, like others in many cities across the country, are not profitable. They don’t generate the revenues needed to maintain them, and are unproductive.

Marohn describes this land use decision model as the Growth Ponzi Scheme. More than 60 years of unproductive growth has buried many cities in financial liabilities.

We’ve simply built in a way that is not financially productive,” he wrote.

Subsidizing Subdivisions

In Lafayette, Strong Towns also found that unexpected parts of the city are profitable – neighborhoods where the city collects more revenue than it spends:

Strong Towns has found the pattern repeated throughout the country. Profitable neighborhoods are often in the oldest parts of cities where buildings first grew up, and then new buildings grew beside them -- block by block. That kind of organic growth generally creates a tax base that can afford the maintenance of the needed public assets and services, Marohn explained.

“It is important to understand that it is a consistent feature we see revealed in city after city after city all over North America. Poor neighborhoods subsidize the affluent; it is a ubiquitous condition of the American development pattern,” wrote Marohn.

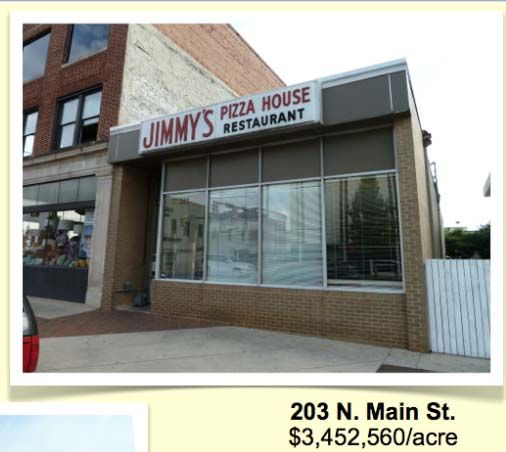

At ICMA, Marohn shared examples that are surprising. In High Point, North Carolina, there’s a mom-and-pop pizza shop in a section of town that offers greater economic value than the big box stores at the edge. Financial productivity is measured in total value per acre, and the contrast is notable:

Strong Towns has found that traditional urban development patterns produce high-yielding properties – not the shovel-ready, utility-ready opportunities located on the outskirts.

Reversing Modern Land Use Trends

According to Marohn, the prescription for reversing the trend is modest investments made over a long period of time. He asked ICMA attendees to go out and walk their neighborhoods.

Our cities are nothing but gaps. Obsess about those gaps,” he advised.

Another tool is finding ways to curb geographic growth and reduce maintenance requirements -- where neighborhoods agree to it.

The city of Memphis has been actively de-annexing neighborhoods since its Strong Towns engagement in 2012.

Years of expansion eventually led to the Tennessee city being stretched to the brink in its efforts to service widespread neighborhoods. The dispersion has led to public safety and other service impacts, and leadership has been working to address it through various initiatives of its Innovation Delivery Team.

One Memphis neighborhood took it upon themselves to demonstrate the possibilities with a pop-up-style experiment staging vacant spaces to show how they could be used to create thriving business. Neighbors went out and painted their own crosswalks and made many small improvements to elevate curb appeal. It worked, Marohn said. Businesses are coming back, profits are going up and the city is studying their process and achievement.

After the Strong Towns engagement, Memphis produced the following infographic to spell out the city’s financial challenges and specify that it would look within the city to make productive use of current infrastructure investments -- rather than continue on a path to horizontal expansion that cannot be maintained: